Augusta hyponatremia

For privacy reasons case reports are written in way to make the patient unidentifiable. The case has been reported to the Italian National Pharmacovigilance Network.

Augusta is an 85-year-old woman with a complex medical history behind her and for which she chronically takes citalopram 20 mg, olmesartan 40 mg and paracetamol 1000 mg if necessary. For more than 30 years she lives with a depressive syndrome resulting from her husband’s premature death, which was followed by the diagnosis of a breast carcinoma for which she underwent a left quadrantectomy. She suffers from hypertension since the age of 53 and five years ago underwent a left knee prosthesis operation, fortunately with a good recovery of mobility. Last month, she had a similar operation on her right knee due to severe gonalgia that had been dragging on for at least two years and caused her many limitations in her daily activities.

After the surgery, fortunately without complications, and a few days in the hospital’s orthopaedic department, Augusta is moved to the rehabilitation centre to begin a programme of intensive physiotherapy. Shortly after her admission by the centre’s staff, following a thorough anamnesis, it emerged that Augusta’s sleep is often disturbed by the continuous urge to move her legs, a condition recognised by the team as compatible with restless legs syndrome, for which she received a therapy with pramipexole 0.18 mg, with an improvement in symptoms.

However, suddenly, eleven days after the operation, Augusta experienced confusion, headache and nausea accompanied by episodes of vomiting. She was promptly submitted to a series of investigations in an attempt to clarify the clinical case: the haematochemical examinations showed severe hyponatremia (serum sodium concentration 113 mmol/L [135 - 145]), in contrast to the immediately preceding days when the parameters were normal.

After careful analysis of the case, probably iatrogenic in origin, Augusta was diagnosed with a syndrome of inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone. A gradual correction of the dysionia was then initiated by administering a hypertonic solution, together with a restriction of the fluid intake and the concomitant discontinuation of the drugs potentially causing the hyponatremia, first and foremost pramipexole, followed by citalopram and olmesartan.

After 4 days of monitoring, the sodium level had risen to 130 mmol/L with complete resolution of neurological symptoms. To complete the picture and dispel any doubts, an abdominal ultrasound and a chest X-ray were performed at Augusta, from which no significant abnormalities emerged.

After few days, with a sigh of relief, Augusta was discharged from the hospital and the follow-up at four months confirmed her complete recovery.

Iatrogenic hyponatremia

Hyponatremia, defined as a blood sodium concentration under 135 mmol/L, is the most common electrolyte disorder observed in inpatient care. In fact, it is estimated that at least 35% of hospitalised patients develop hyponatremia during recovery.1 The main symptoms associated with this condition are neurological (headache, nausea, vomiting, confusion up to lethargy and coma), varying in severity depending on the underlying dysionia and how quickly it occurred. The correction of hyponatremia itself is a challenge for the physician, due to the risk of pontine myelinolysis if the correction is too quick. The reasons for hyponatremia are manifold and depend on changes associated with extracellular volume, so we can speak of hyponatremia with hypovolemia, hyponatremia with euvolemia and hyponatremia with hypervolemia. Based on the individual’s plasma osmolarity, a further distinction can be made between hypotonic forms (with reduced plasma osmolarity) and non-hypotonic forms (with normal or increased plasma osmolarity).2

Plasma osmolarity=2xsodium + Urea2.8 + Blood glucose18

Sodium expressed in mEq/l; Urea mg/dl; glycaemia mg/dl

Augusta’s case was a hypotonic hyponatremia with normal extracellular volume, characterised by a slight excess of water in relation to the body’s sodium level, which was normal. This particular form of hyponatremia is an expression of inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone, which is characterised by hypotonic hyponatremia (plasma osmolarity 100 mOsm/kg), urinary sodium excretion >30 mmol/L with normal sodium and water intake, absence of hypokalaemia, normal renal and thyroid function, and no use of diuretics.3

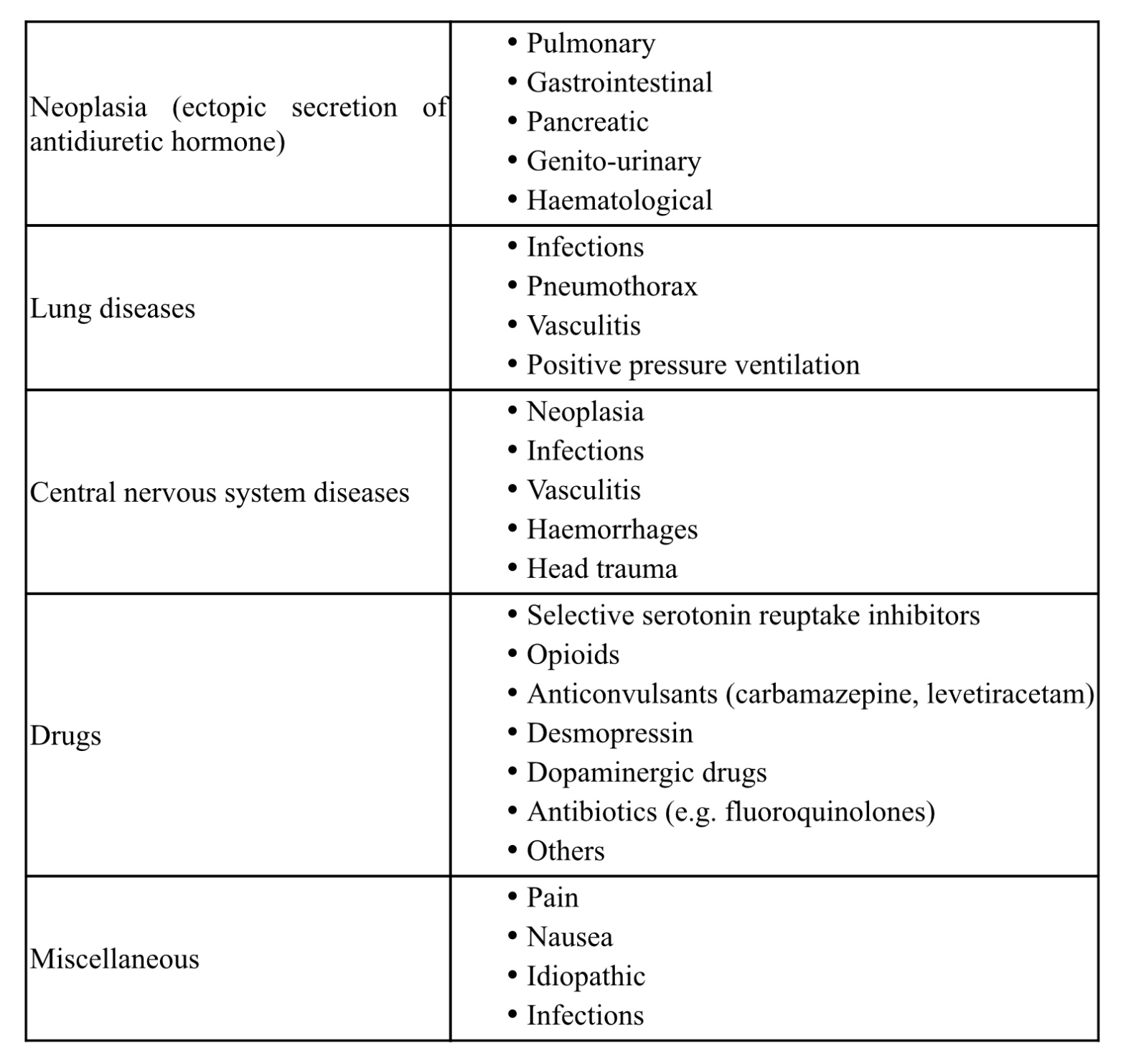

The main causes of syndrome of inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone are summarised in the table.

In order to make a diagnosis of syndrome of inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone, it is important to perform an accurate anamnesis to search out any causes associated with it, paying particular attention to the pharmacological history. The patient’s objective examination is likewise important in order to gain information on the volaemia status, as well as biochemical investigations can provide precious information for the diagnosis.

Many drugs can cause hyponatremia through blood dilution mechanisms (this is the case with some antipsychotics, antidepressants, carbamazepine, cyclophosphamide) or salt loss.2

In Augusta’s case, the recent initiation of pramipexole, in addition to her existing regimen of a sartan and a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, suggests that these drugs may be involved in her clinical presentation. Pramipexole is a highly selective dopamine agonist for dopamine receptors type 2 (D2), type 3 (D3) and type 4 (D4), used in patients with Parkinson’s disease, but also in the treatment of restless legs syndrome. In particular, it appears that pramipexole has, in comparison to other dopamine agonists (cabergoline, pergolide, ropinirole), a high selectivity for the D4 receptor subtype whose stimulation mediates vasopressin secretion, resulting in an increased secretion of the hormone and the development of syndrome of inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone.4 The treatment of these forms of hyponatremia represents a challenge for physicians who, whenever possible, should promptly work to solve the underlying cause, which is crucial for an effective treatment and a favourable prognosis. Correction of symptoms may require several interventions including water restriction (500-1000 ml per day), administration of a hypertonic solution in the case of severe (acute and symptomatic) hyponatremia, and, if insufficient, use of vasopressin V2 receptor antagonists (vaptans). It is also essential to monitor blood sodium levels frequently, avoiding a too rapid correction that could lead to complications such as demyelination.5

Finally, it is important to consider that in the elderly, hyponatremia may be the result of a combination of factors. Distinguishing between syndrome of inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone and hypovolemic hyponatremia secondary to fluid and salt depletion may be complex in this age group, so a careful clinical and biochemical evaluation becomes essential for a correct diagnosis and an appropriate treatment.

M Sartori, E Barbiero, L Pellizzari Geriatrics, Altovicentino Hospital ULSS 7

- Hoorn EJ, Lindemans J, et al. Development of severe hyponatremia in hospitalized patients: treatment-related risk factors and inadequate management. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2006; 21:70-6. CDI

- Canu L, Peri A, et al. Hyponatremia: a case report of SIAD. Clinical Management Issues 2013; v.7, n.2, p 41-52; DOI:10.7175/cmi.v7i2.640.

- Adrogué H, Madias N. The Syndrome of Inappropriate Antidiuresis. N Engl J Med 2023; DOI:10.1056/NEJMcp2210411. PMID: 37851876.

- Arai M, Iwabuchi M. Pramipexole as a possible cause of the syndrome of inappropriate antidiuresis. BMJ Case Rep 2009; DOI:10.1136/bcr.01.2009.1484.

- Martin-Grace J, Tomkins M, et al. Approach to the patient: hyponatremia and the Syndrome of Inappropriate Antidiuresis (SIAD). J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2022; DOI:10.1210/clinem/dgac245.