Off-label drugs in paediatrics: from research to children and back again

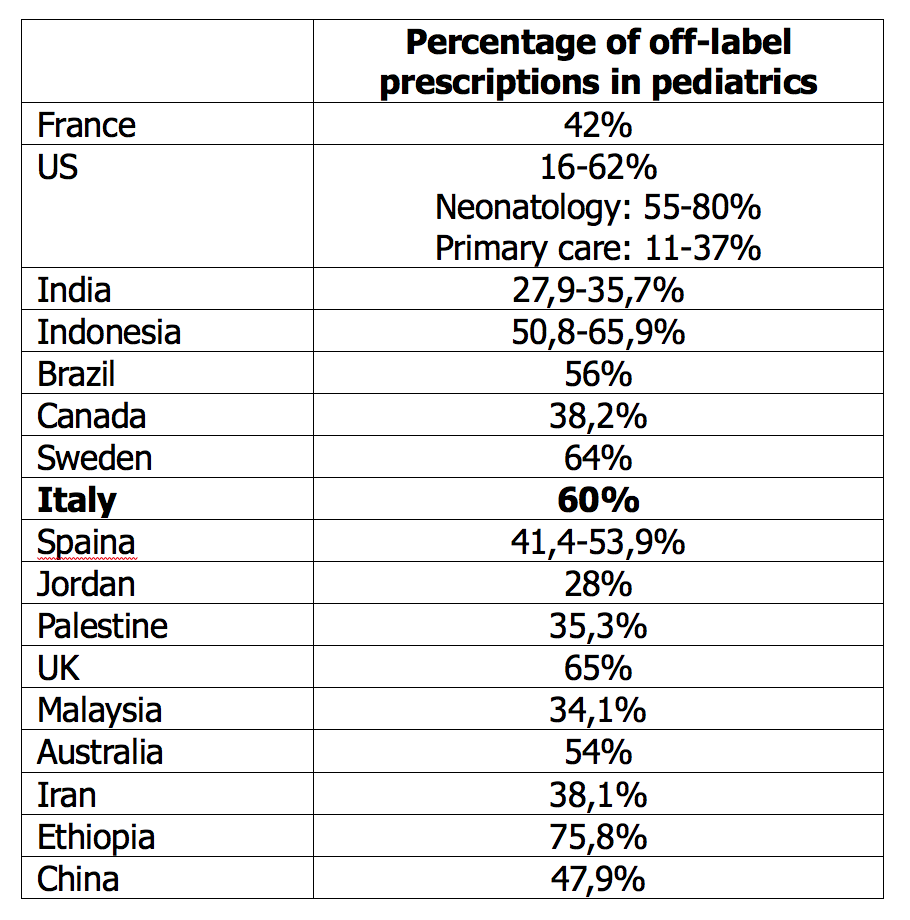

As it often happens - even if it is not always apparent - a single “fil rouge” indissolubly links researchers, pediatricians and children. We are talking about the so-called off-label drugs that represent about 50% of potential prescriptions in the pediatric age. There is a wide range of drugs for which there is not yet an authorization for use in children and that, despite this, are commonly used, all over the world, with indications, dosages and formulations not specifically approved for the pediatric age (Table 1).1-4 This phenomenon affects young children more than adolescents and the hospital setting more than the community care setting.

Table 1. Frequency of pediatric off-label prescriptions in different countries (modified from ref 3)

The reasons for the lack of studies

For researchers (and, consequently, for pharmaceutical companies) the problem lies in the difficulty of conducting studies adequately designed, sized and focused on the correct age target. Without these studies, it is not possible to obtain from the regulatory agencies the necessary authorizations so that the drug can be marketed also for the pediatric age and the relative indication can be reported in the technical sheet. The obstacles that often make this step difficult - and sometimes impracticable - are not few, all widely known and already repeatedly discussed in the literature.5,6

The ethical aspect is the most immediately cogent: children are a vulnerable population, and this constitutes an obvious obstacle to the conduction of clinical trials on issues that are potentially very relevant. On the other hand, when evaluating proposals, ethics committees should avail themselves of particularly expert skills in this field, capable of correctly assessing the relevance of the clinical question and the potential benefits that would derive from the availability of a new therapeutic principle adequately studied for paediatric use. On this aspect, the hope would be that the same regulatory agencies would encourage researchers and pharmaceutical companies to include in their studies pediatric subpopulations if they found that the mechanism of action of a drug could also be of benefit for this age group. Of course, subsequent approval of the pediatric indication would have to meet the efficacy and safety criteria established by each regulatory agency.

It is interesting, in this regard, what is explained in the document of the American Academy of Pediatrics: “The absence of labeling for a specific age group or for a specific disease does not necessarily mean that the use of the drug is inappropriate for that age or for that disease. Rather, it just means that the evidence required by the regulations to allow inclusion in the data sheet (label) was not deemed sufficient by the FDA. Furthermore, lack of labeling in no way means that the therapy is not supported by clinical experience or pediatric data. On the contrary, it specifically means that the evidence of efficacy and safety of the drug in the pediatric population has not been submitted to the FDA or has not met the regulatory standard of ‘substantial evidence’ necessary for FDA approval”.6 It is different - concludes the document - if the technical data sheet states that “safety and efficacy in children have not been established” or if specific warnings or contraindications for the use of that drug in childhood are reported.

Considering the rapid evolution of pharmacological research, it is not surprising that data sheets do not include all the potentially advantageous uses of an active ingredient. In this regard, great importance in the continuous redefinition of the safety of a drug (even if in off-label use) has the post-marketing surveillance and reporting of any adverse events observed.6

The opinion of pediatricians

The point of view of pediatricians is somewhat different and, at the same time, complementary. Faced with a relevant clinical problem (frequent in neonatology and intensive care, for many chronic diseases or rare pathologies) for which the off-label use of a drug could be advantageous, the pediatrician must rely on the best evidence available in the literature, on the opinion of experts or on what is defined for adults. 7 This is a step that, even if it is in the best interest of the patient, requires a careful evaluation of the risk-benefit ratio, the obtaining of a truly informed consent from the parents (and the child himself, if he is able to give it) and, often, the need to produce adequate scientific documentation to support his decision. The feeling may be for the pediatrician to expose himself to an increase in responsibility and for the patient to be the object of an experiment or a therapy of uncertain effectiveness. For both, there may also be a lack of precise awareness of being within a non-codified use of the drug, not to mention that the literature reports a higher incidence of adverse events in the off-label use of drugs in pediatrics.2,8-11

In fact, in the off-label prescription the italian legislation comes to the rescue of the pediatrician and his patient by providing some situations (mainly hospital context) that allow free access to a drug therapy whose marketing has not yet been authorized by the Italian Medicines Agency (AIFA) or that has been but for an indication different from that for which you want to use it.

In Italy there are five paths provided: the first two - Law 648/1996 and Law 326/2003 (AIFA National Fund) - which provide for the reimbursement of the drug, respectively by the National Health Service and AIFA for drugs and diseases included in lists updated periodically; the third considers compassionate use with direct and free supply by the manufacturer of the drug; the fourth allows the non-repetitive use of advanced therapies with preparation provided directly by the manufacturer but with cost charged to the clinical center; the fifth allows access to treatment with a drug regularly on the market but for an indication different from that for which it was authorized (Law 94/98 art. 3, paragraph 2), even in the presence of therapeutic alternatives already authorized. In this case, however, the therapy is paid by the patient or the clinical center in an inpatient setting. All these paths are realized under the responsibility of the prescribing physician.

Off-label in practice

From a practical point of view, it is worth emphasizing two key aspects of off-label use in pediatrics: the first concerns the prescribing pathway and the second the issue of patient safety and therefore the responsibility of the pediatrician. Whether it is an outpatient prescription of ondansetron during gastroenteritis with incoercible vomiting13 or the administration of a biologic drug in hospital, the pediatrician must always be clear about the need to refer to the best available evidence in the literature in terms of efficacy, safety and risk-benefit ratio.

The prescriptive pathway is generally well controlled in the hospital environment where any off-label use must be justified, supported by adequate evidence of efficacy and evaluated by an internal verification team. Less control - and, consequently, more responsibility for the prescribing pediatrician - is perhaps present in the territory and in the direct interaction between the pediatrician and the child and his family. In both cases, it is evident the need for the pediatrician to be always updated not only on the authorizations for the use of a drug, but also on the scientific evidence that evolves over time and that have not yet had time to be officially acquired (best practice).

The implications for the safety of the patient and, consequently, for the responsibility of the prescriber are evident and recall once again the paediatrician’s mandatory obligation to act with awareness and prudence, evaluating the risk-benefit ratio to the best of the knowledge currently available.

In conclusion

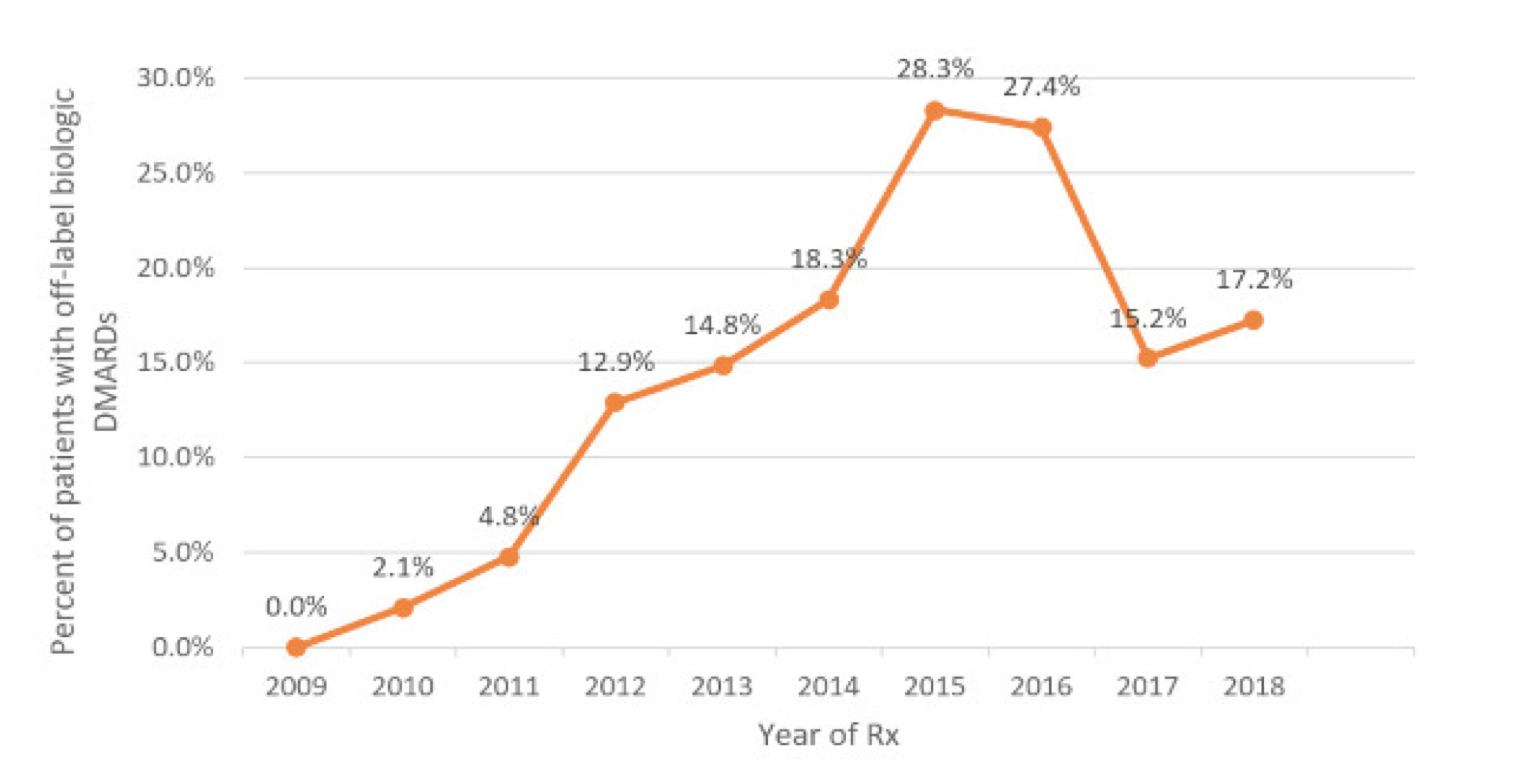

We conclude this article by talking about children, from whose inescapable need for care any off-label prescription should originate. As we have said, the availability of scientifically sound data for the registration of drugs for paediatric use necessarily requires the conduct of studies adequately designed and sized for numbers and age. The goal may not be easily achievable for ethical reasons, consent from parents or even just for the rarity of the disease that prevents the collection of a sufficient number of cases. There are more than 7,000 rare diseases: 80% are genetically determined and affect the pediatric age in half of the cases. Only 5-7% of these diseases have a drug therapy approved by the FDA.14 The use of innovative drugs, such as biologics, occurs in pediatrics outside the approved indications in about 15% of cases, with insufficient evidence of efficacy and increased risk of toxicity and adverse events (Figure 1). The enormous emerging potential of pharmacogenomics represents a new challenge for pediatric drug research and simultaneously increases its necessity and complexity.15

Figure 1. Use of off-label biologics in juvenile idiopathic arthritis in the United States (years 2009-2018)14

Wanting to emphasize the significance of research for the benefit of children, it is worth recalling what AIFA said in a communication campaign 10 years ago, but which still retains its value: “It is necessary to make people understand that the voluntary participation of children and adolescents in clinical trials helps to fill the lack of data, guaranteeing the youngest children greater quality, safety and efficacy of the drugs intended for them”.

Enrico Valletta1, Michele Gangemi2

1 UO Pediatrics, G.B. Morgagni - L. Pierantoni Hospital, AUSL Romagna, Forlì

2 Pediatrician, Verona

- AIFA. Campagna di comunicazione AIFA “Farmaci e Pediatria”. 31 Ottobre 2021, Prot. N. AA/7932/p.

- Balan S, Hassali M, Mak V. Awareness, knowledge and views of off-label prescribing in children: a systematic review. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2015;80:1269-80. CDI

- Shanshal A, Hussain S. Off-label prescribing practice in pediatric settings: pros and cons. Sys Rev Pharm 2021;12:1267-75. CDI

- Sachs A, Avant D, Lee C, et al. Pediatric information in drug product labeling. JAMA 2012;307:1914-5.

- Nuffield Council on Bioethics. Children and clinical research: ethical issues. 14/05/2015. www.nuffieldbioethics.org/children

- Frattarelli D, Galinkin J, Green T, et al. American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Drugs. Off-label use of drugs in children. Pediatrics 2014;133:563-7. CDI

- Balan S, Hassali M, Mak V. Two decades of off-label prescribing in children: a literature review. World J Pediatr 2018;14:528-540. CDI

- Aagaard L, Hansen E. Prescribing of medicines in the Danish paediatric population outwith the licensed age group: characteristics of adverse drug reactions. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2011;71:751-7. CDI

- Wallerstedt S, Brunlof G, Sundstrom A. Rates of spontaneous reports of adverse drug reactions for drugs reported in children: a cross-sectional study with data from the Swedish adverse drug reaction database and the Swedish Prescribed Drug Register. Drug Saf 2011;34:669-82. CDI

- Ufer M, Kimland E, Bergman U. Adverse drug reactions and off‐label prescribing for pediatric outpatients: a one-year survey of spontaneous reports in Sweden. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Safety 2004;13:147-52. NS

- Cliff-Eribo K, Sammons H, Choonara I. Systematic review of pediatric studies of adverse drug reactions from pharmacovigilance databases. Expert Opin Drug Saf 2016;15:1321-8. CDI

- AIFA. Accesso precoce al farmaco e uso off-label. www.aifa.gov.it/accesso-precoce-uso-off-label

- Marchetti F, Bonati M, Maestro A, et al. SONDO (Study ONdansetron vs DOmperidone) Investigators. Oral ondansetron versus domperidone for acute gastroenteritis in pediatric emergency departments: multicenter double blind randomized controlled trial. PLoS One 2016;11:e0165441. CDI

- Fung A, Yue X, Wigle P, et al. Off-label medication use in rare pediatric diseases in the United States. Intractable Rare Dis Res 2021;10:238-45. CDI

- Barker C, Groeneweg G, Maitland-van der Zee A, et al. Pharmacogenomic testing in paediatrics: clinical implementation strategies. Br J Clin Pharmacol