Parkinson’s therapies and pathological gambling

Pathological gambling is attracting increasing attention for high prevalence, involving 0.4-2.2% of the Italian population.1 In the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), pathological gambling is among substance use and addiction related disorders and is defined as “persistent and recurrent problematic behaviour leading to clinically significant impairment or distress”.2 People with pathological gambling persistently think about gambling, are irritable and restless if they try to reduce it, require increasing amounts of money, make numerous unsuccessful attempts to stop, play when they feel anxious or depressed, lie about their involvement in gambling, put at risk social relationships, family and work.2 Pathological gambling is one of the broadest categories of impulse discontrol disorders, including uncontrolled eating disorder, compulsive shopping and hypersexuality.

Parkinson’s disease in Italy has a prevalence of 200-300 cases per 100,000 inhabitants. Pathological gambling and impulse discontrol disorders are present in 14-36% of patients with Parkinson’s disease,3,4 configuring a prevalence 6-90 times greater than the general population.1 Parkinson’s disease is a neurodegenerative disease associated with the progressive loss of neuronal dopaminergic cells in the substantia nigra pars compacta and in the ventro-tegmental area of the midbrain.5 The reduction of dopamine levels in substantia nigra causes typical motor signs (tremor, bradykinesia, muscle hypertonus). Impairment of the ventro-tegmental area contributes to cognitive disorders (working memory deficit and executive functions), depression, and motivation disorders, while other non-motor symptoms (sensory, autonomic, sleep disorders)6 are mainly attributable to the degeneration of non dopaminergic neuronal systems.

Pharmacological therapy for Parkinson’s disease is based on dopaminergic drugs (levodopa, dopamino-agonists, inhibitors of catechol-O-methyl-transferase or mono-aminoxidase) that are effective in improving motor symptoms, but can cause pathological gambling, impulse discontrol disorders and other impulsive-compulsive behaviors such as punding (Table 1), a dopaminergic dysregulation syndrome characterized by excessive dopaminergic therapy intake, similar to drug abuse disorders.7

Table 1. Characteristics of behavioural disorders caused by dopaminergic therapy in Parkinson’s disease (adapted from [6]).

| Punding | Impulse discontrol disturbances | |

|---|---|---|

| Examples of behaviour | Assembling or disassembling objects | Pathological gambling, compulsive shopping, uncontrolled eating disorder, hypersexuality |

| Reason given for the behaviour | Fascination, curiosity | Stress, craving |

| Emotional state during action | Tranquility (as long as the behaviour is not prevented), ego-syntonic behaviour, no attempt to resist the implementation of the behaviour | Euphoria, relief or anxiety; the behavior can be either ego-syntonic or ego-distonic. The patient can try to resist the temptation to perform it. |

| Degree to which behaviour is directed towards a target | Usually without a purpose | Usually directed towards a specific reward |

| Behavior targets | Typically it is about hobbies or work-related interests | Typically aimed at primary or social rewards |

| Degree of stereotyping | Usually highly repetitive tasks | Persistent behaviour, but with a degree of repetition |

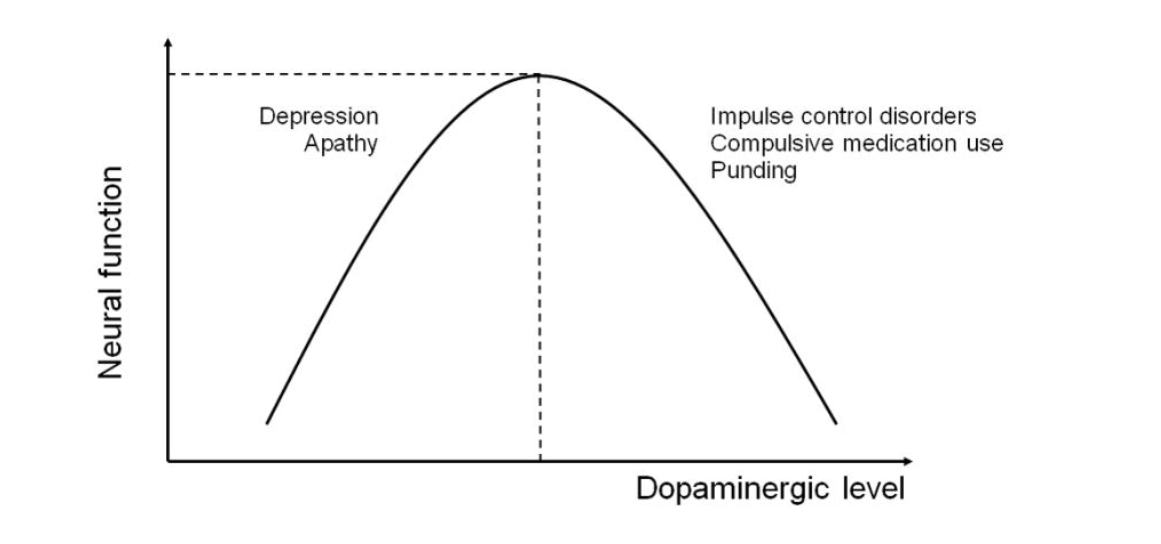

Dopaminergic drugs can result in dopaminergic overdose in brain areas less involved in the neurodegenerative process by determining pathological gambling (Figure 1).8

Figure 1. Levels of dopamine, neural functioning and behaviour8

Too low levels of dopamine (left side of the graph) are associated with minor neural functioning that facilitates the onset of depression or apathy. Dopaminergic therapy to treat the motor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease may cause too high levels of dopamine (right side of the graph) and lead to excessive neural functioning leading to the development of pathological gambling and/or other impulse discontrol disorders.

In the few studies on patients with Parkinson de novo disease or not treated pharmacologically, the prevalence of pathological gambling is 0.9-1.2%.9 comparable to that of the general population.1 In Parkinson’s disease, pathological gambling develops a few months after the onset of dopaminergic therapy or dose increase and tends to resolve when therapy is reduced or discontinued. In a longitudinal study, in de novo patients the incidence of pathological gambling and impulse discontrol disorder increased each year in patients undergoing dopaminergic treatment, while it decreased in untreated patients10 suggesting that chronic treatment or a cumulative dose effect may be critical factors. Iatrogenic pathological gambling is not exclusive to Parkinson’s disease, but may be present in other diseases treated with dopaminergic therapy such as restless legs syndrome although in a smaller number of cases.11

Dopamine agonists appear to be the main responsible for the onset of pathological gambling and impulse discontrol disorder.3 Several studies have sought to highlight possible risk factors for the development of pathological gambling in Parkinson’s disease.

Risk factors for pathological gambling in Parkinson’s disease include: onset of Parkinson’s disease at a younger age, longer duration of disease, socio-demographic factors and habits (not being married, family or personal history of pathological gambling or drug abuse),3 neuropsychiatric factors (anxiety, depression, obsessive-compulsive symptoms, impulsiveness, novelty search) and cognitive factors, in particular involvement of executive functions12.

As in the general population, there are gender differences, as men are at greater risk of developing pathological gambling and hypersexuality, while women are more likely to develop compulsive shopping and uncontrolled eating disorder.3 Patients with Parkinson’s disease with pathological gambling or impulse discontrol disorder have documented changes using neuroimaging13 or scintigraphy14 methods.

Identifying risk factors for pathological gambling in Parkinson’s disease is of extreme importance as the presence of pathological gambling or other impulse disorder is often not brought to clinical attention due to patient embarrassment or lack of awareness. Further longitudinal studies are however necessary to clarify the role of these factors and the cause-effect relationship with pathological gambling.

The treatment of pathological gambling in Parkinson’s disease initially involves the reduction or discontinuation of dopaminergic therapy, in particular dopamine-agonists and substitution with levodopa.15 The drugs tested for pathological gambling in Parkinson’s disease, albeit with preliminary or contradictory results, include the antiglutamatergic agonist amantadine,16 the atypical antipsychotic clozapine17 and the opioid antagonist naltrexone,18 the latter off-label.

Cognitive-behavioural psychotherapy has also shown contradictory effects,19 but may help during the reduction phase of dopaminergic therapy to improve depressive-anxiety symptoms.20

Deep brain stimulation of the subtalamic nucleus allows the reduction of drug therapy, leading in many cases to an improvement in pathological gambling and impulse discontrol disorders, although other studies have documented its worsening or appearance,21 so its role in pathological gambling remains controversial.

Stefano Tamburin

Department of Neuroscience, Biomedicine and Movement, University of Verona; Section of Neurology, Integrated University Hospital, Verona

- Ministero della Salute, Centro Nazionale per la Prevenzione ed il Controllo delle Malattie. Progetto Dipendenze comportamentali/Gioco d’azzardo patologico: progetto sperimentale nazionale di sorveglianza e coordinamento/monitoraggio degli interventi. Regione Piemonte 2012. http://www.ccm-network.it/documenti_Ccm/prg_area5/report-finale_dipenden... (accesso: 11.12.2019)

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5). Arlington: American Psychiatric Publishing, 2013.

- Weintraub D, Koester J, et al. Impulse control disorders in Parkinson disease: a cross-sectional study of 3090 patients. Arch Neurol 2010;67:589-95. CDI

- Callesen M, Weintraub D, et al. Impulsive and compulsive behaviors among Danish patients with Parkinson’s disease: prevalence, depression, and personality. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2014;20:22-6. CDI

- Obeso J, Rodriguez-Oroz M, et al. Pathophysiology of the basal ganglia in Parkinson’s disease. Trends Neurosci 2000;23:S8-19.

- Chaudhuri K, Healy D, et al. Non-motor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease: diagnosis and management. Lancet Neurol 2006;5:235-45. CDI

- Ferrara B, Stacy M. Impulse-control disorders in Parkinson’s disease. CNS Spectr 2008;13:690-8. CDI

- Voon V, Mehta A et al. Impulse control disorders in Parkinson’s disease: recent advances. Curr Opin Neurol 2011;24:324-30. CDI

- Weintraub D, Papay K, et al. Screening for impulse control symptoms in patients with de novo Parkinson disease: a case-control study. Neurology 2013;80:176-80. CDI

- Smith K, Xie S, et al. Incident impulse control disorder symptoms and dopamine transporter imaging in Parkinson disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2016;87:864-70. CDI

- Voon V, Schoerling A, et al. Frequency of impulse control behaviours associated with dopaminergic therapy in restless legs syndrome. BMC Neurol 2011;11:117. CDI

- Martini A, Dal Lago D, et al. Impulse control disorder in Parkinson’s disease: a meta-analysis of cognitive, affective, and motivational correlates. Front Neurol 2018;9:654. CDI

- Biundo R, Weis L, et al. Patterns of cortical thickness associated with impulse control disorders in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord 2015;30:688-95. CDI

- Martini A, Dal Lago D, et al. Dopaminergic neurotransmission in patients with Parkinson’s disease and impulse control disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis of PET and SPECT studies. Front Neurol 2018;9:1018. CDI

- Voon V, Napier T, et al. Impulse control disorders and levodopa-induced dyskinesias in Parkinson’s disease: an update. Lancet Neurol 2017;16:238-50. CDI

- Thomas A, Bonanni L, et al. Pathological gambling in parkinson disease is reduced by amantadine. Ann Neurol 2010;68:400-4. CDI

- Rotondo A, Bosco D, et al. Clozapine for medication-related pathological gambling in Parkinson disease. Mov Disord 2010;25:1994-5. CDI

- Papay K, Xie S, et al. Naltrexone for impulse control disorders in Parkinson disease: a placebo-controlled study. Neurology 2014;83:826-33. CDI

- Okai D, Askey-Jones S, et al. Trial of CBT for impulse control behaviors affecting Parkinson patients and their caregivers. Neurology 2013;80:792-9. CDI

- Dobkin R, Menza M, et al. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for depression in Parkinson’s disease: a randomized, controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry 2011;168:1066-74. CDI

- Amami P, Dekker I, et al. Impulse control behaviours in patients with Parkinson’s disease after subthalamic deep brain stimulation: de novo cases and 3-year follow-up. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2015;86:562-4. CDI