Inflammatory bowel disease and biosimilars

Over the last 20 years, biological drugs have changed the therapeutic prospect for chronic inflammatory bowel diseases both in the adult and in the child.1 Infliximab was the first drug that, when its patent expired, had biosimilars authorised by EMA, CT-P13 and SB2 respectively in 2013 and 2016.2 The commercialisation of the biosimilars has injected competition in an extremely delicate and expensive sector for the drug industry, with the result that the European Countries have registered a decrease in the official costs of infliximab between 2 and 39%, with peaks over 70% in Norway.2,3,4

The initial (and unjustified) diffidence towards biosimilars

Initially, clinicians greeted biosimilar drugs with a certain degree of skepticism. In some corporate contexts, the prescriptive pressure, whose nature is essentially economic, contributed to overshadow the scientific premises that allowed their development and commercialisation. These doubts – at least in regard to their use for chronic inflammatory bowel disease – were echoed by the cautious positions of some international and national scientific societies.5,6

Without any intent of diminishing their beneficial effects as market price moderators and therefore their potential in terms of equality of access, economic sustainability and resource redistribution for the National Health Service, the world of biosimilars is in reality much more complex and rigidly regulated.7-9

Summing up quite broadly, the “biosimilarity” of a new product is founded on principles that include the equivalence of its productive quality in respect to the biological of reference, but also the equivalence in bioavailability, therapy effectiveness and safety, besides the necessity of withstanding post-authorisation surveillance - that in the last 10 years has highlighted no significant difference in terms of adverse reactions between biosimilars and their originators.7,10

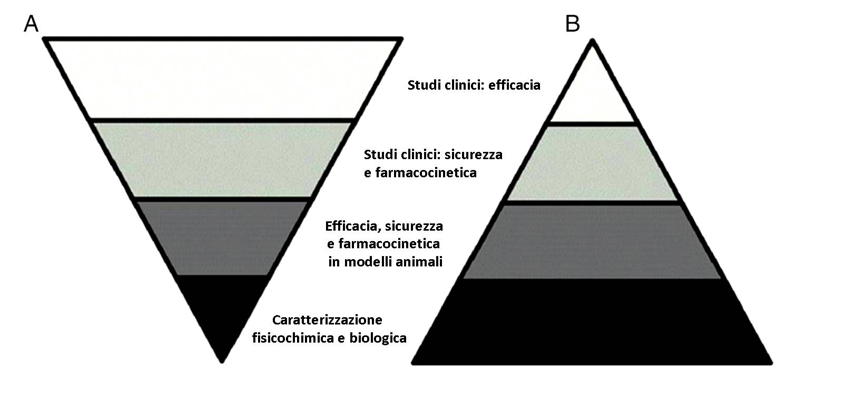

After all, the process that leads to the registration of the originator is conceptually different from the one that guides the approval of the biosimilar: in the first one the focus is on the clinical evidences of effectiveness (clinical studies), in the second one what prevails are the procedures for gradual comparison and comparability with the reference drug (see figure).11

Figure. Difference in the process for the development of an originator drug (A) and of a biosimilar (B) (modified by ref. 11)

Biosimilars in children with chronic inflammatory bowel diseases

On the basis of the authorisation tests and the positive feedbacks gathered from adult patients, biosimilars started being used also for the treatment of chronic bowel diseases in children.12,13 The very few studies available are encouraging,14-16 but even the most recent literature calls for a deeper understanding and attentive pharmacovigilance for this age group, which is critical under many aspects.11,17 Two of these, in particular, are underlined. The first one concerns the judgement of interchangeability between biological and biosimilar, which has been attributed on the basis of data collected from different pathologies (rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis) and in adult patients. Chronic inflammatory bowel diseases in the child are particularly demanding illnesses, the drug physiology and clearance are different than in the adult and the immunogenetics of biosimilar infliximab should also be better investigates on the long term. The second aspect that has been debated concerns the possibility for a child already in therapy with the originator drug to switch (perhaps automatically) to the biosimilar. The only one multicentre clinical experience carried out in Poland on 39 children with chronic inflammatory bowel diseases seems to indicate that the switch is doable and safe but, obviously, more data are needed.14,17 In regard to both these points, EMA does not provide stringent indications and directs to the dispositions elaborated by the single member countries.7 In Italy, AIFA acknowledges that the choice of the drug – biological or biosimilar – is, in ultimate analysis, responsibility of the prescriber, de facto excluding the possibility of an automatic switch.8

In conclusion – as often happens in pediatric age – the scarcity of specific studies, on one hand, induces to an understandable caution in adopting therapeutic strategies derived from adult treatments, but from the other one risks to deprive Pediatrics of important therapeutic resources, which are in very rapid evolution and are accessible also in economically challenging contexts. Regulatory agencies and clinicians doubtlessly agree on the necessity of further clinical studies and strict post-marketing surveillance (study ReFLECT and CONNECT – chronic inflammatory bowel diseases, https://clinicaltrials.gov). And another important biological used for the treatment of chronic inflammatory bowel diseases, adalimumab, will lose its patent in Europe next year and the commercialisation of its biosimilar ZRC-3197 started in India already in 2014.13

- J Clin Gastroenterol 2017;51:100-10.

- Curr Opin Pediatr 2017;DOI:10.1097/MOP.0000000000000529

- QuintilesIMS. The Impact of Biosimilar Competition in Europe, May 2017

- OsMed. Rapporto Nazionale 2016. AIFA 2017

- J Crohn Colitis 2013;7:586-9. CDI

- Dig Liver Dis 2014;46:963-8. CDI

- EMA-EC. Biosimilars in the EU. 27 April 2017

- AIFA. Second concept paper sui farmaci biosimilari. 15 Giugno 2016

- J Crohn Colitis 2017;11:26-34. CDI

- Ricerca & Pratica 2014;30:216-7

- J Ped Gastroenterol Nutr 2015;61:503-8. CDI

- BioDrugs 2017;31:37-49.

- World J Gastroenterol 2017;23:197-203. CDI

- J Crohn Colitis 2016;10:127-32. CDI

- Ther Adv Gastroenterol 2016;9:729-35. CDI

- J Ped Gastroenterol Nutr 2017;DOI:10.1097/MPG.0000000000001670

- J Ped Gastroenterol Nutr 2017;65:134-6.