Drug Safety. Whose Responsibility?

University of Liverpool, former chairman of MHRA

When a medicine is marketed, much is known about its quality and pharmacology and in its efficacy in a carefully screened group of patients in clinical trials. These data, however, may provide an incomplete and even misleading account of the drug’s effectiveness in the community at large. Even less is known at the time of marketing approval about its safety in the general population, because of the size of the clinical trials and the selected nature of the subjects included. In other words, its overall benefit-risk balance is uncertain.

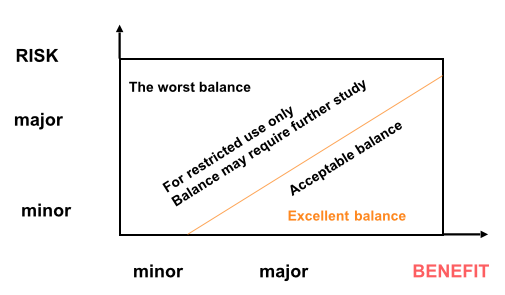

It is important to consider a drug’s benefit-risk balance rather than merely its safety (Fig.1). Many drugs with apparently horrendous safety profiles (e.g, anticancer agents) are used very successfully in skilled hands because of their effectiveness and hence , favourable benefit-risk balance. So instead of discussing drug safety, we should be considering benefit risk balance.

Several stakeholders have responsibilities for ensuring drug safety after marketing.

Fig.1: The Benefit-Risk Spectrum

1. Health care professionals.

The responsibility of those who prescribe a drug includes the recording of any harms that it causes, but also to extend the knowledge of its benefit risk balance

- The documentation of harm uses mainly techniques of passive surveillance to generate signals of drug safety. Reports of adverse events are reported to regulatory authorities who can take several possible actions. First, they provide feedback to the prescribing community. Second, they can issue warnings (e.g.Black Box warnings in US). Finally they can limit prescribing to certain groups of patients , or by specially qualified doctors . Thirdly they can remove the marketing authorisation for the medicine.

- Extending knowledge of drug safety.

Observational studies or, more rarely, clinical trials are used to extend knowledge of drug safety, using active surveillance techniques. Active surveillance is defined as “a systematic approach to population based drug safety surveillance which seeks to ascertain completely the number of adverse events by means of a continuous pre-organised process”. For such studies, clinical data is collected from patient records ( e.g. electronic health records, or the UK Clinical Practice Research Datalink), from Patient Registers (e.g. British Rheumatological Society register of all patients on anti-TNF anti-inflammatory drugs), or rarely from clinical trials in which the endpoint is drug safety.

2. Regulators

Drug regulation has its basis in ensuring the safety of medicines, and over the years, seminal events have led to new regulations. The adulteration of an elixir of a sulphonamide with ethylene glycol (used instead of glycerol) in 1937 in US led to provisions to ensure the quality of medicines. The thalidomide disaster in the 1960s resulted in premarketing requirements to ensure the safety and efficacy of marketed medicines. More recently, the consequences of the administration of the monoclonal antibody TG1412 to volunteers in a phase 1 clinical trial resulted in new regulations for first in man studies of new molecules.

All regulatory authorities update their safety requirements.

In Europe, new pharmacovigilance regulations were introduced in 2012 which emphasised the importance of risk management plans for all newly approved products, improved the the legal basis for post authorisation of safety and effectiveness, and sought to improve transparency of and access to safety information which had hitherto been the sole preserve of regulators but was now extended to other interested parties. In US, the Food and Drugs Administration Amendments Act of 2007 defined the post marketing requirements and commitments for market authorisation holders. These requirements could comprise information gained from adverse event surveillance, observational studies or clinical trials. The Act also defined Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies (REMS) which could be applied to new medicines or to medicines where new safety hazards had been observed.

The Act also proposed a new active safety surveillance system known as Sentinel. Mini-Sentinel programmes have been established as a preliminary for the major Sentinel project. These programmes are pilot studies using electronic data such as Electronic Health Records (EHRs) and claims data to evaluate the safety of marketed drugs and medical devices. As of September 2013, the Mini-Sentinel data base contains information on 360 million person years of information and 4 billion pharmaceutical dispensings. It is proposed that the Sentinel programme will provide information on post marketing safety and effectiveness of marketed medicines and also be used for safety signal evaluation. It promises to be a research database for high quality pharmacoepidemiology.

3. Industry

Industry has the statutory responsibility to report to regulatory authorities all adverse drug events which health care professionals or patients report to them. Interestingly, in UK most patients tend report such events to doctors, whereas in US, these reports are more often transmitted directly to industry. Apart from this, Periodic Safety Update Reports (PSURs) in Europe and Periodic Adverse Experience Reports (PADERs) in US are interval data safety reviews of products, have now evolved into Periodic Benefit Risk Evaluation Reports (PBRERs) which have to be completed by industry and forwarded to regulatory authorities. PBRERs review risk in the context of benefit and seriousness of the condition being treated, reflect ing the appreciation that consideration of safety issues should be replaced by benefit-risk assessment discussed above.

4. The patient

The patient is the most important stakeholder of drug safety. Unfortunately the voice of the patient is often not listened to. Patients naturally wish to know which symptoms they may encounter from the prescription medicines they take. Consulting the Adverse Reaction section of the label, they will find a wealth of information. But what they may not realise is that this information is largely gathered during clinical trials and is based almost entirely on clinicians' impressions and interpretation of patients' symptoms, rather than first hand reports of patients' experiences with the drug.

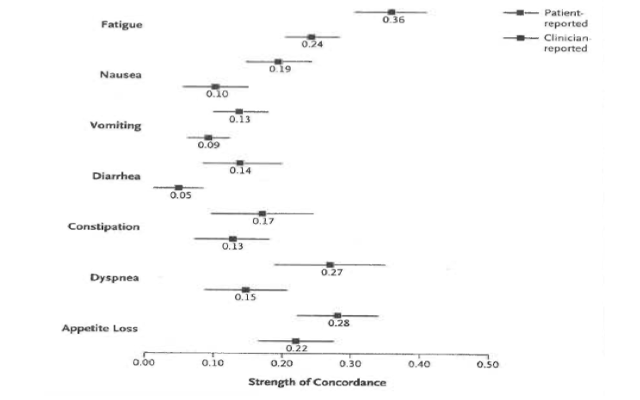

There is now a substantial body of evidence that this assumption may be wrong and that clinicians systematically downgrade the severity of patients' symptoms. Patients'reports frequently capture side effects that clinicians fail to appreciate. The figure 2 illustrates the non concordance between patient and clinician appreciation of adverse events in a group of 467 patients with various forms of cancer treated at the Sloan Kettering Institute in New York.

Fig 2: Patient v Clinician Symptom Reporting

There are no regulatory requirements that clinicians' rather than patients'reports should be used in clinical trial data; all that regulators ask is that sponsors provide safety data during drug development and approval. Paradoxically regulatory authorities give encouragement to patient reported outcome measures during drug development to support labelling claims.

It is not as if there were a lack of instruments for collecting data from patients both during drug development and after marketing authorisation. This is especially relevant for subjective symptoms.

One important method which is being increasingly used comes under the general title of Social Media. This can be defined as "The social interaction among people in which they create, share or exchange information and ideas in virtual communities and networks. "Social media depend on mobile and web-based technologies. They differ from traditional or industrial media in many ways , including quality, reach, usability and permanence.

There are several types of social media-collaborative projects( e.g Wikipedia),blogs and microblogs (e.g. Twitter), social networking sites (e.g. Facebook), and content communities (e.g.You Tube) but the difference between these is becoming increasingly blurred.

One important point relevant to the present discussion is that medicines regulatory authorities increasingly realise that social media may represent methods of communication among communities to which previously they had no access. It has been estimated that some 10% of interactions in various forms of social media relate to health matters, among which drug therapy is an important component.

So many medicines regulatory authorities - EMA, FDA and National Competent Authorities are now investing heavily in this form of communication and are using it to not only to provide alerts to important safety messages, but also to listen to discussions on current issues and to give invitations to receive feedback.

One important area which is emerging from social media exchanges is the continuing effectiveness of medicines. There has been great emphasis over the years by regulators, politicians and the press on the safety of medicines rather than their effectiveness in the wider community after marketing authorisation. Once efficacy has been established in clinical trials , effectiveness in community use has been assumed. Conversations in social media are now challenging this.

Conclusions

The assessment of safety, or more appropriately of benefit risk balance, is a shared responsibility. Prescribers,industry and patients must all interact with regulatory authorities using the most relevant available tools. Increasing attention is being paid to the voice of the patient and the impact of social media techniques is still to be fully realised. As methods of marketing authorisation evolve which allow medicines to be made available earlier in their life cycle, the importance of these forms of assessment will become yet more important.

- Clin Pharm Therap 2009;85:241-6. CDI

- Clin Pharm Therap 2012;92:486-93. CDI